Without Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s groundbreaking work, many significant astronomical discoveries would not have been possible. We might not know that our universe is expanding, or that it’s been around for over 13.7 billion years, or that the Milky Way is more than 100,000 light-years in diameter. Let’s explore and celebrate the contributions of this talented astronomer who was once hired as a “human computer”.

Developing an Interest in Astronomy

Henrietta Swan Leavitt was born on July 4, 1868, in Lancaster, Massachusetts. She studied at Oberlin College in Ohio before transferring to the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which later became Radcliffe College. In her final year there, she took an astronomy class and developed a lifelong interest in the stars. After graduation in 1892, she volunteered as a research assistant at the Harvard College Observatory. Little else is known about Leavitt’s early life.

A portrait of Henrietta Swan Leavitt. Licensed in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Discoveries at the Observatory

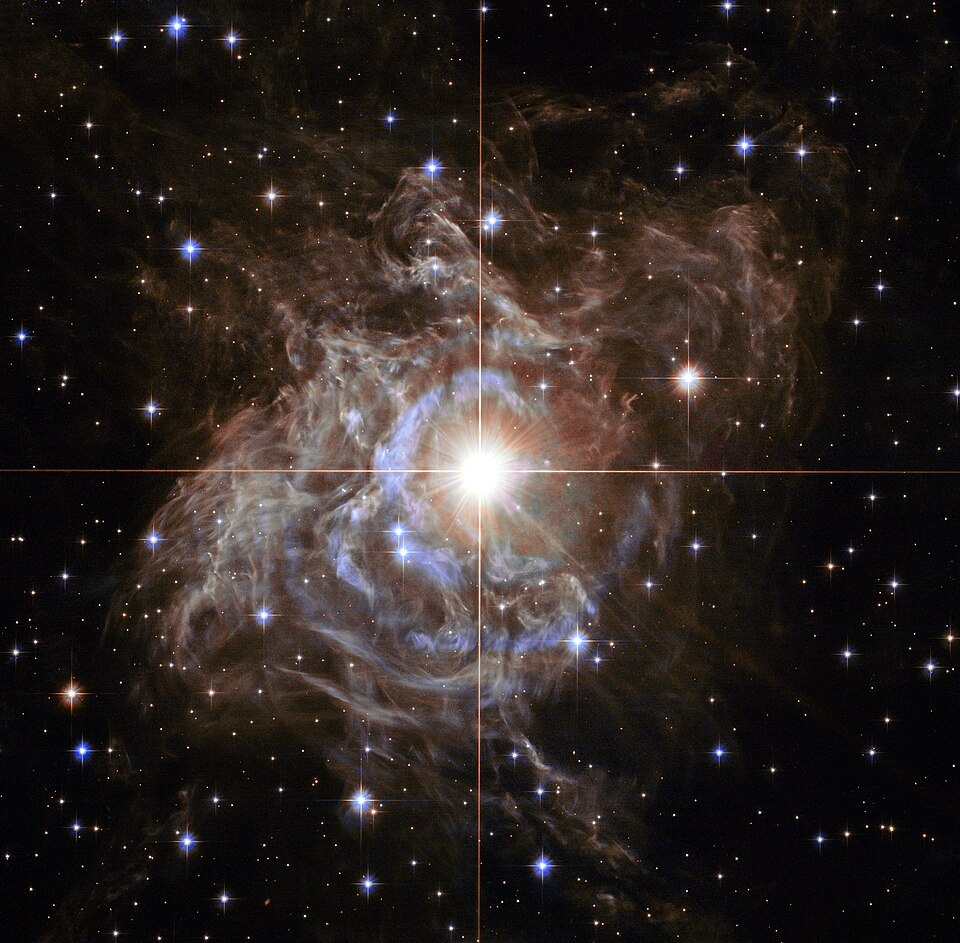

Following her work as a research assistant, Leavitt was hired by Edward C. Pickering, an astronomer at the Harvard Observatory, to work as a “human computer”. This position required her to measure and catalog stars based on their color and brightness. The work was done by hand, comparing photographs of stars recorded on glass plates. These photographs were taken at the same location in the sky, and Leavitt had to repeatedly and patiently identify the magnitude of the stars in the photos taken day after day. Leavitt was specifically assigned the task of analyzing variable Cepheids, a type of star that varies in diameter, temperature, and brightness.

An image of RS Puppis, one of the brightest Cepheid variable stars in the Milky Way, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. Licensed in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Original photograph taken by NASA.

Leavitt left the university to work as an art assistant at her family home, but after six years, was drawn back into the world of astronomy and returned to the observatory in 1903. She was promoted to head of the stellar photometry department, where she continued investigating stars and categorizing their brightness. Over the course of her work, she discovered roughly 2400 variable stars and 4 novas.

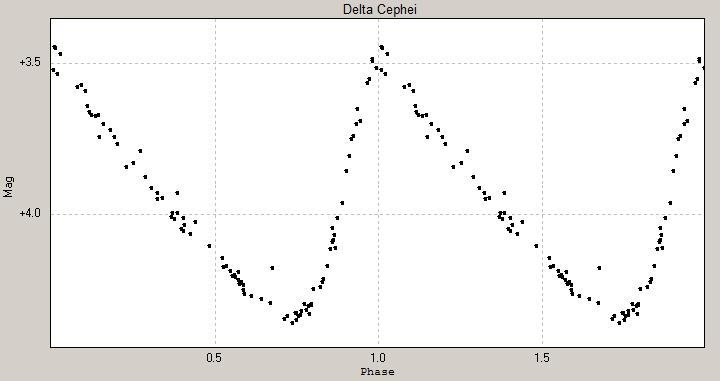

It was during this time that she noticed a pattern — the brighter a variable star was, the longer its pulses were. Because she knew that the variable stars she was studying were relatively close to each other, she could infer that the brightness of Cepheids had nothing to do with distance. By comparing the brightness of stars and the length of their pulses, this allowed astronomers to calculate distances in space. This relation between the brightness and pulse length became known as the period-luminosity relation.

The light curve graph of variable star Delta Cephei. Notice the regular wave-like pattern of the pulses. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Leavitt’s Legacy

While, sadly, Leavitt did not live to see the effects of her discovery, her work paved the way for future scientists to make other astonishing findings. For example, her work allowed for the creation of a “standard candle”, a variable Cepheid that helps in measuring astronomical distances. By finding the distance to Cepheid stars, one could measure the distance to other nearby stars. This allowed Edwin Hubble, for example, to determine that the universe is expanding, not static, and that it is much larger than previously believed. Although Leavitt’s hard work wasn’t recognized at the time, she greatly impacted the course of astronomy. To honor her contributions, the period-luminosity relation was renamed “Leavitt’s Law” in 2008.

Further Reading

- Learn more about Leavitt’s life and work here:

- Read about others who reached for the stars here:

- Caroline Herschel Manufacturing, a luminary astronomer who discovered multiple comets and star clusters and laid the foundation for the star catalog

- Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, a theoretical physicist who found that certain dying stars will form into extremely dense alternative bodies

Comments (0)